Today, December 1, is the feast of St. Charles de Foucauld – his first since being officially canonized by Pope Francis this past May. We find it appropriate, then, to present an adapted translation of this piece from the Osservatorio, which was published on the occasion of his canonization day.

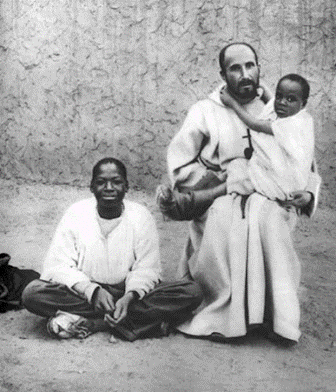

St. Charles was an authentic apostle of the Gospel who burned with desire to make “his” Jesus known and loved. He lived among the Touareg in the Algerian Sahara:

I live here, a lone European… Happy to be alone with Jesus, only for Jesus.

Like every such event, St. Charles’ canonization involved and touched the whole Church, and especially the 19 families of lay people and priests who are drawn to his spirituality. However, there is also an “illegitimate child” who feels involved and almost united with the new saint: Kiko Argüello, founder of the Neocatechumenal Way.

In fact, on the Neocatechumenal Way’s official website, an article was dedicated to the canonization of Brother Charles, written by Fr. Ezechiele Pasotti, in which it is stated that, with Kiko, there are “various and profound ties, and they go from the moment of their conversion to the insight of life hidden among the poor, to the way of being ‘poor among the poor,’ to the ‘dream’ of an adoration chapel on the Mount of the Beatitudes.”

We want to analyze, one by one, these alleged links between the saint whose feast we today celebrate and the one who, with so much insistence, for more than half a century claims to be his faithful imitator.

Conversion

Charles de Foucauld, after an adolescence lived far from the faith and immersed in the pleasures of an easy and comfortable life, began to experience an existential restlessness during a dangerous exploration in Morocco. Returning to France, he continued his research, stimulated by good examples of Christian people.

I started going to church, without being a believer. I was not happy except in that place, and I spent long hours there, repeating a strange prayer: “My God, if you exist, let me know You!”

With the help of a holy priest, Father Huvelin, he found his faith and returned to the Sacraments in 1886 at the age of 28.

As I believed that there was a God, I understood that I could not help but live for Him alone.

The journey of Brother Charles, from the day of his interior renewal, continued on his passionate search for Christ, lovingly tracing his footsteps one by one, in such a way that his life is both a faithful imitation of Jesus and a loss of himself in the “Beloved.”

I love Our Lord Jesus Christ and I cannot bear to to lead a life other than His… I do not want to go through life in the first class, when the One I love has gone through it in the last class…

Kiko also had an existential crisis and a conversion, but his goal was not the one professed by Charles de Foucauld, to follow the example of Christ.

He explains later, in his Guidelines for the Conversion Phase (the manuscript of the initial catechesis):

Jesus Christ is not at all an ideal of life to be accomplished through your efforts…

Many people think Jesus Christ came only to give us a more perfect law than the earlier one and, with his life and his death (especially his sufferings) to give us an example so that we can do the same. For these people, Jesus Christ is only an ideal, a model of life…

If Jesus Christ had come only to give us an ideal for living, how could he have given us such a high ideal, so high, that no one can achieve it?

p. 118-119

The Passionist theologian Fr. Enrico Zoffoli commented on this, which he described without hesitation as “nonsense,” writing: “Kiko ignores that the Gospel is the existential message that ultimately boils down to the wisest, most loving and heroic following of Christ, pushed to think, feel, live like him, in and for him (Phil 2:5).”

What did Charles de Foucauld think of the possibility and necessity of imitating Christ? He wrote:

Let us take advantage of the example of the saints, but without stopping for a long time or taking this or that saint as a complete model, and predicting of each what seems to us most in conformity with the words and examples of Our Lord Jesus Christ, our only and true model, thus making use of their lessons – not to imitate them, but to better imitate Jesus.

In fact, he expounded his own spiritual formula in this way:

Imitation is inseparable from love. It is the secret of my life: I lost my heart for this Jesus of Nazareth crucified nineteen hundred years ago and I spend my life trying to imitate him as far as my weakness allows.

This is how, after having consecrated himself to God as a Trappist monk, thirsty for greater poverty, greater penance, and greater conformity to Jesus, with the approval of his superiors and spiritual director, he left La Trappe and went to Nazareth as a hermit in a monastery of Poor Clares. His aim was to “lead the life of Our Lord as faithfully as possible, living only by manual labor and following all his advice to the letter…”

The idea, the purpose, and the transposition in the life of Brother Charles of Jesus in following Christ and in conforming oneself to him is completely antithetical to that of Francisco “Kiko” Argüello.

Life Hidden Among the Poor

Charles de Foucauld wanted to deepen his vocation through a sort of hermit’s life, in prayer, adoration, silent work, and great poverty. This initially took place in the Holy Land with the Poor Clares of Nazareth.

Brother Charles wished to share this “life of Nazareth” with other brothers. For this, he wrote the Rule of the Little Brothers, which he codifies as a “family life around the consecrated Host.”

My rule is so closely linked to the cult of the Holy Eucharist that it is impossible for many to observe it without there being a priest and a tabernacle; only when I become a priest will it be possible to have an oratory around which to gather and only then may I have some companions…

Returning to his own country again, he was ordained a priest at the age of 43 in the Diocese of Viviers. But, Africa was calling him again and so he went to the Sahara Desert of Algeria, first to Beni Abbès, one of the poorest of the poor, then further south to Tamanrasset with the Hoggar Touareg.

Kiko Argüello, according to the article on the Way’s website, followed step by step in the saint’s footsteps. The article reports a statement by the Spanish founder:

De Foucauld gave me the formula to realize my monastic ideal: to live as a poor man among the poor, sharing their homes, their work, and their lives, without asking anyone for anything and without doing anything special.

We do not know exactly what Kiko did together with Carmen in the poor neighborhood of Palomeras in Madrid. What is certain is that they stayed there for a short time, and almost immediately tried to export the experience of “fraternity” – experienced in particular with a colony of gypsies who had settled in that area – in the rich parishes of Madrid. Extreme poverty, after having experienced it for themselves, was by no means their ideal of life. Charles de Foucauld’s ideal was very different from theirs!

An example of Kiko Argüello’s total indifference to the apostolate among the outcasts of society is his arrival, together with Carmen Hernández, in Italy.

Father Dino Torreggiani, the two Spaniards’ first ecclesiastical sponsor on Italian soil, had believed in the authenticity of their vaunted experiences among the poor of Madrid and had great hopes and expectations of them as “apostles of the long-haired” (Hippie sympathizers) who camped out day and night in Piazza Navona.

But Kiko, who landed in the capital for this mission, turned out to be a real disaster. He didn’t want to know how to evangelize the hippies: he slept late, went to movies…; as Kiko himself confided to Fr. Cuppini, presbyter in their team before Fr. Pezzi, his “inspiration-aspiration” was exclusively that of going to Rome to get closer to the Pope (and enter into his good graces). [From the book Interview with Francesco Cuppini by Tarcisio Zanni.]

Father Francesco Cuppini himself notes as “interesting” the fact that the first parish “evangelized” by Kiko and Carmen in Rome was that of the Canadian Martyrs. In fact, he writes, “from one who lived in the slums, one could more logically expect an apostolate aimed at the poor, a community of the poor, a bit like Madrid.” But, he concludes: “Instead, the Lord here in Rome passed the Way directly from the shacks to the bourgeois.” So, according to Cuppini’s notion, it was God who wanted it, making the two Iberians’ (themselves bourgeois) great love for Marian poverty evaporate in so short a time. It is essential to remember that from this point on, this “breath of life” hidden among the poor will never again be part of the objectives of the two founders of the Neocatechumenal Way.

The Dream of an Adoration Chapel on the Mount of the Beatitudes

Charles de Foucauld wrote:

…I believe it is my duty to strive to acquire the probable site of the Mount of the Beatitudes, to secure possession of it for the Church and then transfer it to the Franciscans, and then to strive to build an altar where, in perpetuity, there may be celebrated Mass every day, and Our Lord may remain present in the tabernacle…

On this, the saint reflects and prays so much that he also sets the date: April 26, 1900, the feast of Our Lady of Good Counsel. And he is deeply convinced that his vocation to “imitate Our Lord Jesus as perfectly as possible, in his hidden life” will receive a more radical and definitive consecration here on the Mount of the Beatitudes.

There I will be able to be infinitely more for my neighbor, for my only offering of the Holy Sacrifice… arranging a tabernacle which, with the mere presence of the Blessed Sacrament, will invisibly sanctify all the surroundings, in the same way in which Our Lord in his mother’s womb sanctified the house of John [the Baptist]… as well as with the pilgrims… with the hospitality, almsgiving, and charity that I will try to practice towards everyone.

In this regard, it seems appropriate to remember Kiko and Carmen’s contempt for the tabernacle, and their lukewarmness towards the Real Presence and the adoration of the Blessed Sacrament.

Kiko said in the Guidelines for the Conversion Phase:

We Christians do not have altars in this sense because the holy stone is Christ, the only cornerstone. That’s why we can celebrate the Eucharist on a suitable table and we can celebrate in a square, in the countryside or wherever it is suitable. We don’t have a particular place where exclusively we should celebrate our worship.

p. 51-52

And Carmen supported him by declaring:

I always say this to the Sacramentarians who build immense tabernacles: if Jesus Christ had wanted the Eucharist to be there, he would have made himself present in a stone that doesn’t go bad.

p. 329, unedited Italian edition

She goes on to describe the deviance of

…the adoration, the genuflections during Mass at every moment, the elevation for all to adore… In the Middle Ages the bell was rung at the elevation, and those who were in the countryside worshipped the Blessed Sacrament.

p. 331, unedited Italian edition

Given these premises, it is normal that they end up declaring that

…the conflicts with the Protestants are disappearing because by going to the center, essentially, we will agree with them.

p. 162, unedited Italian edition. Compare with the watered down rephrasing on p. 173 of the approved English edition

According to Kiko and Carmen, we will agree with the Protestants, not vice versa!

The difference between the vision of Kiko and Carmen, on which they have instructed all their followers and has never been explicitly rejected, and that of Brother Charles de Foucauld is ever more abysmal.

In an open letter, a pained and scandalized member of one of the fraternities inspired by the example of Brother Charles’ life expresses well how much the luxurious mausoleum of the Domus Galilaeae–with its circular chapel, weighed down by the Kikian bronze group–corresponds to de Foucauld’s ideal.

Finally, after having spoken of the imitation of Christ, of the hidden life with the poor, and of adoration in front of the tabernacle which were the foundations on which Charles de Foucauld was sanctified, and with respect to which Kiko Argüello and Carmen Hernández instead chose a path totally at the antipodes, we conclude with Brother Charles’ idea of Christian evangelization.

Charles de Foucauld’s evangelization is

not through words, but through the presence of the Blessed Sacrament; the offering of the Divine Sacrifice; prayer; penance; the practice of Gospel virtues; charity, a fraternal and universal charity that shares even the last bite of bread with any stranger who presents himself, and that receives anyone as a beloved brother…

Learning the Gospel lesson, “Whatever you do to one of these little ones, you have done to me,” he always opens the door when someone knocks, breaking his contemplative solitude. He wrote:

From 4:30 in the morning to 8:30 in the evening, I can’t stop talking to, seeing people: slaves, the poor, the sick, soldiers, travelers, onlookers.

His life passed like this, inside his enclosure, without going out to preach, but ready to host anyone who passed by, be he friend or foe.

What a difference with the verbose, redundant, constricting, extravagant, elitist, divisive, noisy, self-referential “evangelization” of Kiko, Carmen, and the Neocatechumenal Way!

Saint Charles de Foucauld, we entrust to you in prayer all those who still believe in the absurd claims of holiness and catholicity of the Neocatechumenal Way as desired by its founders, so that, considering your example and virtue, they reject without further delay the fictions and inauthenticity which keep them bound. Amen.

Leave a comment